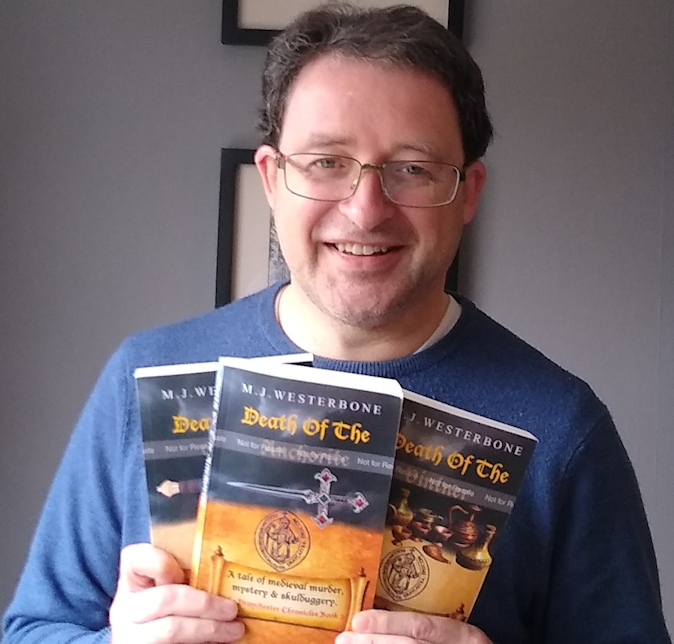

March Update…

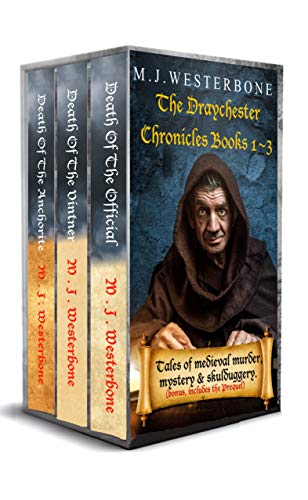

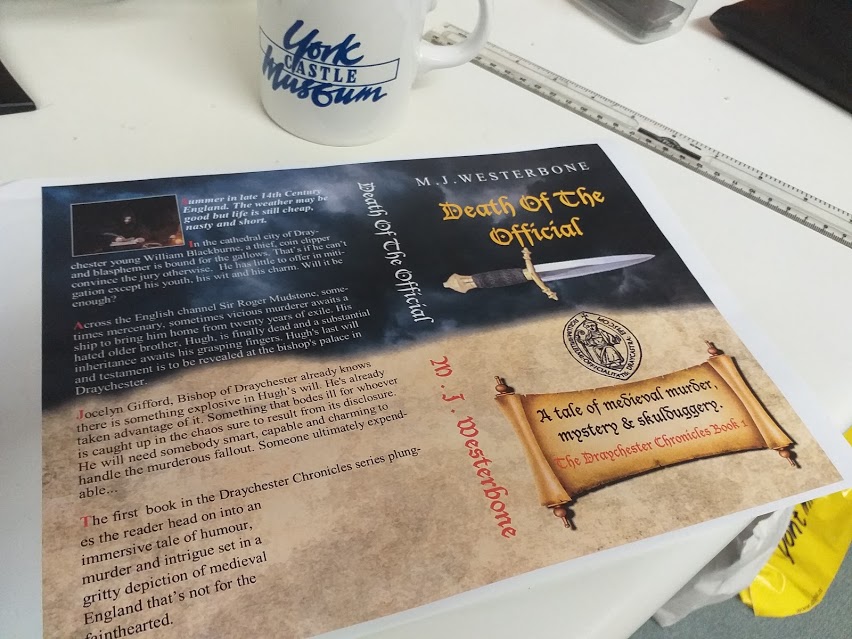

The New Omnibus Edition – Draychester Chronicles 1-3 & the prequel all in one place for the first time.

March, and spring time is not far away here in northern England. It’s been a long winter in many ways and like most of us I am looking forward to better days ahead. Still, there’s some time yet to sit by the fire and read about times past, or, in my case, write about them.

Over the last few weeks I have made great progress on the fourth book in my new Draychester Chronicles series. Will, Bernard and Osbert, in the “Death of the Wakeman”, are once again heading north from Draychester to investigate more medieval, murder, mystery and skulduggery in late 14th century England. I am looking at a release date probably towards the end of spring if things go to plan.

Although book four is a fair few weeks away I do have news of a new omnibus edition which contains not only books one through three but also the prequel book as well! So if you want to jump right in, all 800+ kindle pages of medieval murder are available right now…(it’s also available as a paperback… when you’ve read it you can reuse it as a door stop, it’s that thick…)

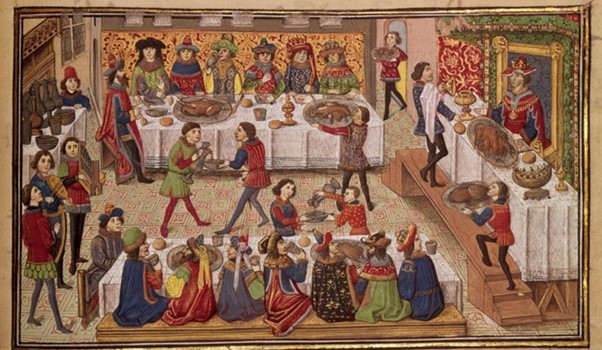

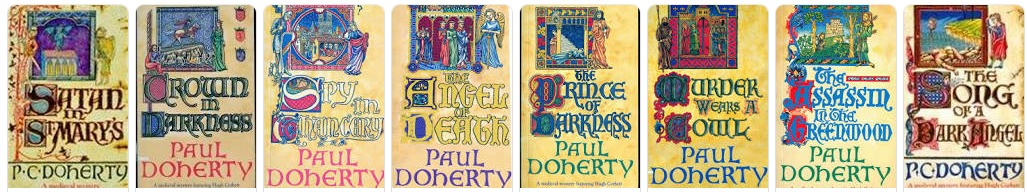

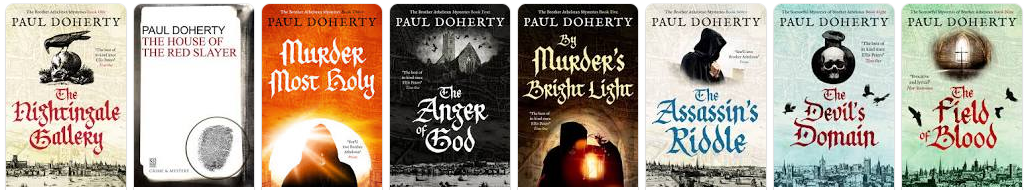

I first came across Paul Doherty’s books via his Hugh Corbett series, set during the 13th-century reign of Edward I of England. There are now twenty-one books in the series as of 2020’s “Hymn to Murder”. I have loved this series since the first book was published back in the late 1980s. Doherty has written something like 100+ published works under a variety of pen names alongside his real name. The sheer volume and quality of his literary output is quite amazing. The other series of his I’m familiar with is the “Sorrowful Mysteries of Brother Athelstan”, set during the 14th-century reign of Richard II of England. Again a great read. The series will be on book twenty as of December 2020. I highly recommend both series, Doherty is an absolute master of the historical mystery genre.

I first came across Paul Doherty’s books via his Hugh Corbett series, set during the 13th-century reign of Edward I of England. There are now twenty-one books in the series as of 2020’s “Hymn to Murder”. I have loved this series since the first book was published back in the late 1980s. Doherty has written something like 100+ published works under a variety of pen names alongside his real name. The sheer volume and quality of his literary output is quite amazing. The other series of his I’m familiar with is the “Sorrowful Mysteries of Brother Athelstan”, set during the 14th-century reign of Richard II of England. Again a great read. The series will be on book twenty as of December 2020. I highly recommend both series, Doherty is an absolute master of the historical mystery genre.