A Medieval Christmas

The church, which dominated so many aspects of medieval life, ensured that Christmas was a true religious holiday and a highlight of the calendar. It was the longest holiday of the year, twelve days, lasting from the night of Christmas Eve, the 24th of December, to the Twelfth Day, Epiphany, on the 6th of January. Mid-winter saw a lull in agricultural tasks and meant that everyone got the chance to enjoy some of the merriment and festivities.

Then as now, it was a season that involved decorating the home with garlands and wreaths. William Fitzstephen (a cleric and administrator in the service of Thomas Becket) writing in the 12th century recorded,

“Every man’s house, as also their parish churches, was decked with holly, ivy, bay and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green.”

The local parish church would be the focal point of the celebrations with Nativity plays and other festive traditions observed.

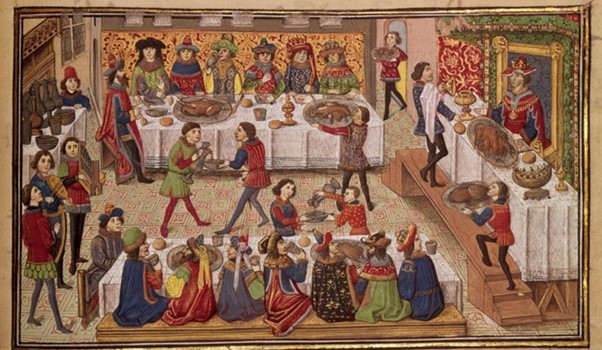

Feasting was of course a major part of the celebration. The humbler members of the community might treat themselves to a rare delicacy of some meat, cheese and eggs. On the menu for the local clergy and lord of the manor might be such things as Larks, ducks, salmon, even wild boar. At the other end of the spectrum was the royal court…

On Christmas day 1213, King John, spending the festive period at Windsor Castle, held a feast. The sheer quantities and logistics concerning the organisation of the feast boggle the mind. In charge was Reginald de Cornhill, a long-time administrator under King John.

We can only imagine the stress poor Reginald must have been under. With only around a week’s grace, he suddenly found himself with the task of finding,

“20 tuns of good and new ordinary wine, both French and Gascon, and 4 tuns (2 of red, 2 of white) for the king’s table. 200 pigs’ heads with all the pickled pork, 1,000 hens, 50 pounds of pepper, 2 pounds of saffron, 100 pounds of good fresh almonds and 15,000 herrings, as well as spices for making sauces, two dozen towels and 1,000 ells of linen for making tablecloths”.

Other officials were tasked with finding even more provisions, including another 200 pigs’ heads, 15,000 hens and 10,000 salted eels. They also needed to lay their hands on all the pitchers, cups and dishes they could find.

You might have thought, given the severe financial pressures John found himself under during his rule, that this sort of extravagance might have attracted some criticism! However, from a medieval perspective, displays of royal generosity were expected, indeed they a were a key part of medieval politics and in fact the chroniclers of the time approved whole heartedly with his largess. He was only doing what was expected of a medieval king.